Can deep value investors really expect the outstanding returns attributed to negative enterprise value stocks?

Imagine that you're shopping for houses when you happen upon a cozy looking cottage in a nice neighbourhood. The realtor takes you through the place. It has a good sized yard, a shaded patio, cedar siding, and was originally built by a real craftsman with love & care.

There are problems with the house, though. It needs a new roof and the heating is broken. You have a rough idea of what these will cost to fix, about $30,000, so you factor those into the price you're willing to pay.

But then the realtor drops a bomb: The seller doesn't want anything to do with these problems. He's eyeing a place in a hot neighbourhood across the city. So, the owner is willing to walk away form the house for only $300,000, which is $200,000 LESS than other houses in the neighbourhood. It's a definite bargain.

But that's not all. Blushing, the realtor pulls out a wooden chest storing stacks of $100 bills, $400,000 total. "This comes with the house."

Your jaw drops, not sure what to say. Instead, you reach out your hand to shake on the deal.

Instead of paying $300,000 for a cozy little cottage, the owner has just PAID YOU to take the house off his hands. The transaction works out to you claiming a FREE house PLUS $100,000 in cash. This is exactly why so many deep value investors are excited about negative enterprise value stocks.

Event Driven Daily's guide will walk you through exactly what negative enterprise value stocks are, how they come about, the risk and returns associated with them, and whether you should include them as part of your portfolio.

Read on to get a detailed look at this fascinating deep value strategy.

What Is Enterprise Value?

You'd be forgiven if you never heard the term before. Enterprise Value is an esoteric term to those without degrees in finance or investors who have slipped deep down the value investing rabbit hole.

But, you've probably heard of the term market capitalization, before. Market cap is the sum total market value of all outstanding common shares a company has issued. For example, Apple 's market cap at the time of writing is $755 billion USD. Each Apple share is trading for $145 and there are 5.21 billion shares outstanding.

5.21 billion shares

x $145 per share

= $755 market cap

If you wanted to buy all of Apple's shares at today's share price, it would cost you $755 billion to do so. (Incidentally, if you have that kind of money, email me.)

But that's not all that the company would cost. If you take over ownership of the entire company, you also take over responsibility for the company's debt - its bank debt, issued bonds, lines of credit, etc. You would have to pay these off eventually, so it's a cost you assume to buy a firm.

Taking over the company would also give you full control of the company's cash and cash equivalents, however. Some companies have more cash than they need to run the business, so that cash is free to be used to invest in new projects, or return to shareholders in the form of share buybacks or dividends.

In fact, adding all this together - the company's market cap, total debt, and excess cash - is a much better way to assess the true price of a corporation. Folks in finance have dubbed this combination "enterprise value."

In Apple's Case, on top of its $755 market cap, the company also had $99 billion in total debt and $67 billion in cash as of its April 1st, 2017 balance sheet. Totalling these three up, we get an enterprise value of $787 billion. This is the true cost to acquire the firm.

$755B market cap

+ $99B total debt

- $67B cash & cash equiv

= $787 enterprise value

You can also put enterprise value on a per share basis if you want to assess the true cost of a slice of that business (a.k.a. the true cost of a stock). In this case, we simply take Apple's enterprise value ($787B) and divide it by the company's outstanding shares (5.21B) to get its enterprise value per share ($151.06).

Don't let the term "enterprise value" fool you. In value investing we normally reserve the word "value" for what an investor gets (remember Buffett's quote: "Price is what you pay, value is what you get."). In this this case, the word "value" could be swapped with the word "cost" which would more accurately reflect the concept. Enterprise value is the total cost of acquiring a company.

What Is Negative Enterprise Value?

What is negative enterprise value? How could enterprise value possibly be negative?

Simple.

Look at our enterprise value equation one more time:

market cap

+ total debt

- cash & cash equiv

= enterprise value

We start with market cap and then add total debt before subtracting cash and cash equivalents. If cash and equivalents are large enough, we end up with a negative number.

Let's assume Apple had $900B in cash and re-evaluate its enterprise value:

$755B market cap

+ $99B total debt

- $900B cash & cash equiv

= -$46 enterprise value

$900 billion is a staggering amount of cash for a company to have, but it's illustrative. The end result is that Apple has an enterprise value of -$46 billion.

When enterprise value turns negative, you should sit up and pay attention. In the hypothetical example above, if you acquired the entire company, you would shell out $755B in cash to acquire all the shares and assume $99B in total debt for a total acquisition price of $854 billion... but you'd get $900 billion in cash for your trouble... so you would end up with a FREE company PLUS $46 billion in cash to spend on pizza. It would be the deal of the century!

How Do Negative Enterprise Value Stocks Come About?

At first glance this deal seems too good to be true. Who would give you $46 billion dollars for taking ownership of Apple? The short answer is that nobody would today, but there are companies that offer investors this unbelievable bargain right now.

Nobody will just hand you a company and a stack of cash, unfortunately. In fact, if a company does have net cash on its books then it also usually has a market cap that's trading well above net cash. Net cash is always a bonus because it can be used for new projects, paid out in dividends, or used for share buybacks to boost per share value, but it's not exactly the same as getting a free company and a stack of cash.

For a company to actually trade below its net cash value, for it to trade as a negative enterprise value company, it usually has to be going through a large business problem. Deep value bargains don't surface for no reason - they are usually the result of major issues with a company. Even in the house example we used at the start of this article, the house needed a new roof and the heat wasn't working.

When investors see problems in a company, fewer investors want to buy the company and the price drops. If the problems are large enough, investors tend to run from the business like mice from a cat. Investors don't like anything to do with business problems but this gut reaction makes for massive opportunity for shrewd deep value investors like us.

While most investors look at the income statement and buy companies that are earning exceptional profits, keeping an eye on the balance sheet can allow you to scoop up major assets for a fraction of their true value. Investors then profit if the business recovers, investors recognize the mis-pricing, there's a 3rd party takeover of the firm, or the business decides to liquidate. This is deep value investing at its finest.

Returns To Negative Enterprise Value Stocks

As you probably expected, returns for negative enterprise value stocks have been very good. So far there hasn't been much published on this strategy, however. In fact, we've only found one study on these investments.

The Alon Bochman Negative Enterprise Value Backtest

The study was conducted by Alon Bochman, CFA, who looked at the returns to negative enterprise value stocks between 1972 and 2012. While he was careful to make sure his performance results were not affected by look-ahead bias, he made no mention of survivorship bias which may have boosted returns well above what real world investors should expect. Survivorship bias occurs when the sample of stocks that you're studying does not include companies that went bankrupt or were delisted, causing your results to be arbitrarily inflated.

Bochman found 2,613 stocks with a negative enterprise value in the United States over the 40 year period. That works out to just a hair over 65 companies per year - highlighting just how rare these opportunities are!

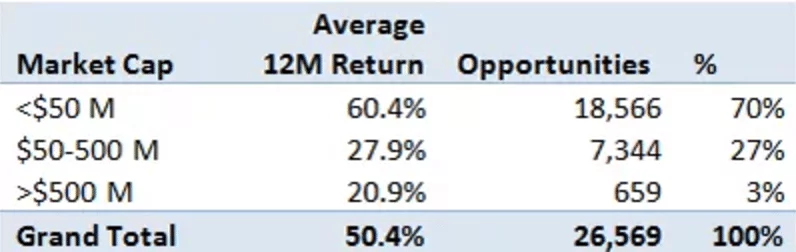

Despite the possible survivorship bias, Bochman's numbers were exceptional. Take a look:

Roughly 70% of all negative enterprise value firms had market caps below $50 million USD, so these were tiny companies. The average negative enterprise value stock in this group returned a staggering 60%!

Keep in mind, also, that his stated 60% is not a compound annual average return (CAGR) for the strategy. It's the average negative enterprise value stock return, which is quite different. It does not reflect the portfolio performance that negative enterprise value investors should expect from their portfolios over the long term.

Returns to larger companies were quite a bit lower, as well. Firms with market caps between $50 and 500 million produced an average return of 28% while the few negative enterprise value firms with market caps above $500 million produced an average return of 21%.

Compound Annual Returns Versus Average Annual Returns

Again, these are average returns and not a CAGR. Here's why this is important…

Portfolio returns…

Year 1: 100%

Year 2: - 50%

Year 3: +100%

Year 4: - 50%

Year 5: +100%

Year 6: - 50%

Average annual return = 25%

Compound annual return = 0%

The average annual return is just the arithmetic average… and does not necessarily indicate your portfolio's growth rate. The compound annual return (CAGR) is also known as the geometric return and is used for calculating the growth rate for your portfolio. Despite the average annual 25% return, your portfolio didn't grow.

Event Driven Daily's Negative Enterprise Value Backtest

We're not content with the knowledge available for any single strategy until we have a time to test it and study the results. The same is true of negative enterprise value investing.

We tested a plain vanilla American negative enterprise value strategy from the start of 1999 until the end of 2016 - a period of 17 years. Our universe was made up of all US stocks that produced financial statements, had market caps above $1 millon USD, and had at least $2,000 in average daily trading volume so that tiny investors could realistically buy stock.

Our study also accounted for both survivorship bias and look-ahead bias, to ensure more robust results; and, rather than looking at the average return a negative enterprise value stock produced, we look at the portfolio's compound annual growth rate along with a few other metrics. This gives us a better idea of how a typical real-world investor would have faired investing in the strategy.

We bought our stocks and formed an equal weight portfolio at the beginning of the year and then rebalanced our portfolio exactly 12 months later. Every time we bought or sold a stock we incurred a 2% slippage fee (a reduction in our holding's value) to reflect issues that may be incurred buying and selling stocks.

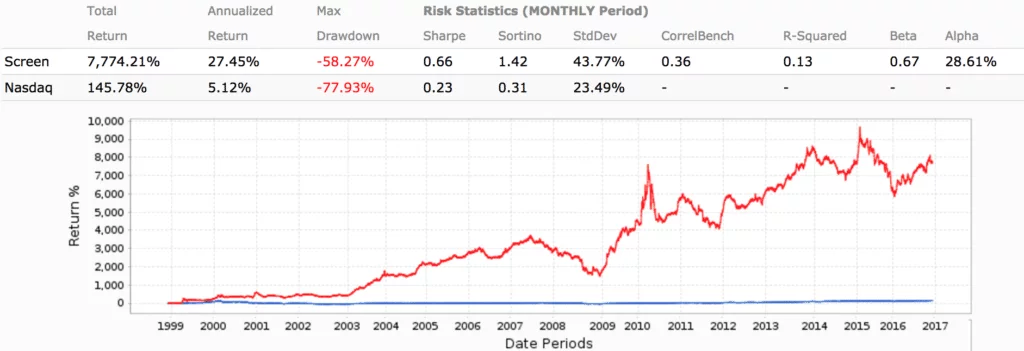

The results were fantastic:

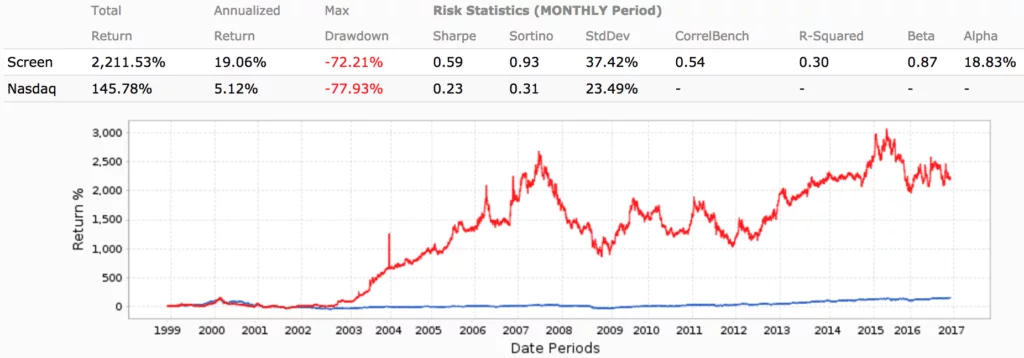

The first thing you'll notice is the last red line rapidly moving up and to the right. The returns to even a plain vanilla negative enterprise value stock strategy are great! In this case, the compound annual growth rate amounted to 27.45% compared to the NASDAQ's weak 5.12% returns for the period!

An investor employing this strategy would have earned a total return of 7,774%. Put into perspective, $10,000 would have become $780,000 over the 17 year period. Outstanding!

Breaking up the 17 period into 3 chunks, we see just how the strategy performs under different market periods.

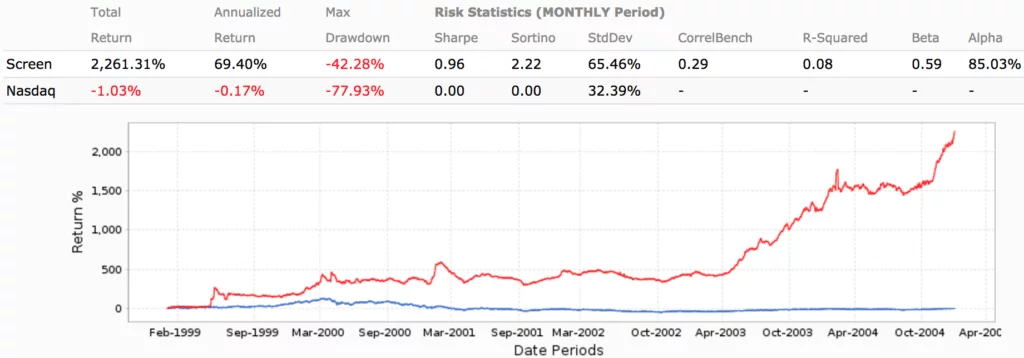

The strategy performed very well from 1999 to 2005. While there was a long period where the strategy had essentially no returns, it also dodged the major market meltdown caused by the dotcom bust. For the end of the period, the strategy earned an outstanding 69.4% compound average return. Most of the return came from the market rebound starting in April of 2003 and the 1999 bull market.

The strategy did not perform as well over the next 5 years, from 2005 to 2010. While negative enterprise value stocks beat the market handily, the CAGR was only 15.6%. The negative enterprise value strategy survived the Great Financial Crisis, recoding a -41% drop in value during 2008 versus a -42% decline for the NASDAQ. Again, most of the excess returns came during the rebound in 2009.

The post-Great Financial Crisis period has been a bad time for value investing, while FANG stocks (Facebook, Amazon, Netflix, Google) have been largely responsible for pulling up the major market indices. It's not surprising then that returns were even worse for negative enterprise value stocks during this period. More disappointing, while no year saw a large negative return, in 2015 your portfolio would have surged ahead and then dropped by a large -44%. The drawdowns in these three periods highlight some of the volatility that negative enterprise value investors experience.

Negative enterprise value stocks perform very well so long as you are prepared to stick with the strategy over the long term. The strategy can either perform exceptionally well, as in the 69.4% compound annual returns seen between 1999 and 2005, or disappoint, as in the 2010 to 2017 period. To reap the 27.5% return attributed to the strategy, an investor would have had to stick with it over the entire period, maintaining a fully invested portfolio.

Negative Enterprise Value Stocks: No Free Lunch

It's clear that our model portfolio above provides fantastic long term performance… but there's a catch: our portfolio held between 62 and 350 stocks in any single year. I don't know about you but I find it tough to manage a portfolio with 350 stocks.

In fact, I've found it tough to deal with a portfolio of more than 20 stocks. Remember, even if you're buying all of your holdings at once based on a simple set of criteria and waiting 12 months to rebalance, you still have to examine the actual financial statements of each company to make sure that the stated standardized figures (for example, the financial statements presented by Google Finance) are correct. Standardized financials commonly have errors, so you need to conduct due diligence to make sure that you're actually buying firms that fit your screen.

20 stocks seems manageable… so what happens when we limit our portfolio holdings to 20 stocks?

The strategy performs dramatically worse. Our CAGR drops by a third, from 27.45% to 19.06%, pulling our Sortino Ratio down from 1.42 to .93. The Sortino Ratio is a performance measure that tracks upside performance against downside volatility. The higher the figure, the better.

But, the portfolio's maximum drawdown of 72% would really shake the nerves of deep value investors. Sometime during your holding period, you would have watched your portfolio erode in value by nearly 3/4ths. This is an earth shattering drop that would have tested the confidence of even the strongest deep value practitioners.

Deep value investors have to keep diversification top of mind. Since we're buying distressed businesses, not all of them may work out and some will even go bankrupt. To illustrate, James Montier assessed the performance of net nets and found that about 5% of the firms saw a massive stock drop of 90% or more (compared to 2% of stocks generally). While downsides cannot be eliminated, they can be reduced dramatically through additional criteria and your portfolio can become much more stable & reliable with more diversification. In this context, the performance of negative enterprise value stocks is crazy since we consider a 20 stock portfolio well diversified.

Is Negative Enterprise Value Investing Dead?

From this writeup, it's clear that negative enterprise value investing seems problematic. The tremendous performance of these sort of stocks will continue to lure deep value investors who want to earn exceptional returns but do not fully understand the risk that they're taking on.

If you want to invest in negative enterprise value firms, you have to find a way to hold a concentrated portfolio while maintaining exceptional long term returns, and limiting both the strategy's volatility and the maximum drawdown. We've found this process exceptionally difficult, but don't give up hope. Perhaps some strong qualitative factors can really up the performance. More to come...

Read next: Bubbles And Busts: How Value Investors Can Profit